This article was published on: 05/22/21 3:48 PM

County is experiencing its driest spring in 127 years

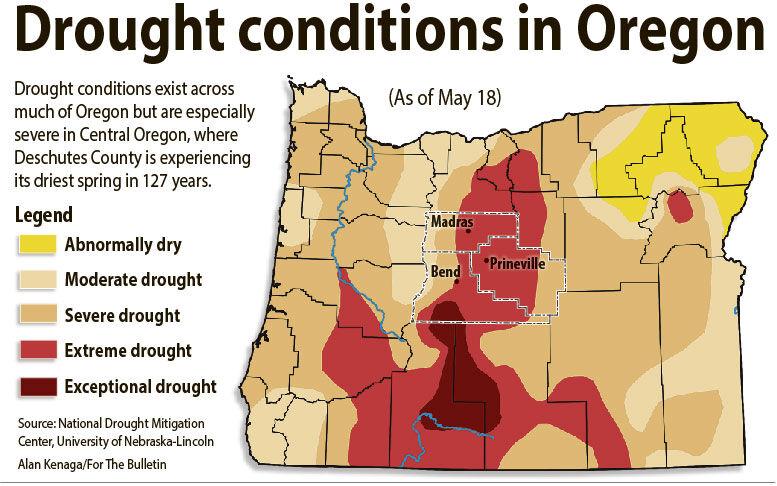

Deschutes County is going through its driest spring since records started 127 years ago. That fact combined with low levels of water in the Central Oregon reservoirs has prompted irrigators to seek a drought declaration from the state.

On Wednesday the Deschutes Basin Board of Control sent a letter to the Deschutes County Commission requesting the drought declaration. The commissioners will consider the request when they meet this

An official declaration of drought, recognized by the governor, allows farmers to tap into state and federal financial assistance programs. The financial assistance could help farmers who aren’t able to plant on all their acres due to water restrictions.

The Deschutes Basin Board of Control comprises eight irrigation districts, including Arnold, Central Oregon, Lone Pine, North Unit, Ochoco, Swalley, Three Sisters and Tumalo. Collectively they convey water to over 150,000 acres of farms and ranches, as well as local cities, parks, and schools.

The letter, written by basin board president Craig Horrell, requests that county commissioners declare a state of drought and they, in turn, ask Gov. Kate Brown to issue an executive order recognizing the severe drought.

“The DBBC believes County action and support from the state is needed,” Horrell stated in the letter. “This may include assistance from the Oregon Water Resources Department and other Oregon executive branch agencies, operating within their statutory authorities.”

Horrell added that the dry conditions could cause “widespread and severe damage” to a number of sectors and industries, including agriculture and livestock, natural resources, and tourism.

For farmers, the tight water supply reduces the number of acres on which they can plant crops, leaving them less revenue at the end of the year. A drought declaration allows farmers to receive funds through their crop insurance plans.

Precisely how much is available varies based on the farmer and his or her situation, said Rob Rastovich, a Deschutes County rancher. Rastovich said he attempted to apply for government assistance last year but did not qualify. But the amount of money wasn’t much, he added — less than $5,000. That sum was a fraction of the amount he had to spend to buy hay for his cows. Rastovich said he doesn’t have crop insurance.

“It’s very expensive. Not many people I know pay for it,” said Rastovich.

As farmers work to conserve water, the irrigation districts themselves are also at risk of running out of their annual allotment of water. Last year, Arnold Irrigation District was forced to shut off its water to customers in mid-August due to the low flows.

Last month, commissioners from Jefferson County requested a drought declaration for their county. Brown has yet to confirm the drought status.

The dry ground and exposed fields in Jefferson County have set the stage for dust storms that blow away topsoil and make driving hazardous.

“Soil blowing off the land is more than a hardship for farmers,” said Gail Snyder, founder of Coalition for the Deschutes, a nonprofit that brings together conservationists, farmers and others to protect the Deschutes River. “It is a bad situation for all of us. The dust bowl of the 1930s was not an aberration that will never happen again.”

Phil Chang, one of three county commissioners, said in an email that he plans to vote to request the governor declare a drought.

“I do think a drought declaration is warranted,” said Chang. “Our reservoirs are really empty, and the snowpack is melting off very quickly without increasing the flow in creeks and the river much.”

Chang, a career resource manager, said multiple years of low groundwater recharge are resulting in “very thirsty ground” which is absorbing snowmelt without much discharge from springs to creeks and rivers.

Larry O’Neill, State Climatologist at Oregon State

University, said drought conditions in Deschutes County are worse now compared to a year ago, when much of the county was in a state of severe drought.

Deschutes County is in the midst of its driest March to April period on record, spanning 127 years, he added. The past two years have been the second-driest two-year stretch during that time. The only drier period occurred in 1932, during the Dust Bowl era.

“This drought in Central Oregon is not just about the short-term deficits, but is a product of an extremely dry last three wet seasons,” said O’Neill. “This drought is shaping up to be one of the worst ever for Central Oregon.”