Capital Press: Sweeping changes to Oregon water law approved in 2025

By Mateusz Perkowski

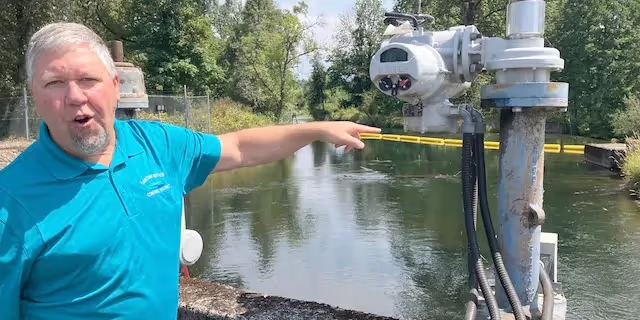

Though modernizing Oregon water law is a laudable target, irrigation district manager Brent Stevenson isn’t yet sure if lawmakers hit the bullseye this year.

It will take time to know if the tweaks and alterations to state water law approved in 2025 were wide of the mark, since they’ll require time for regulators and irrigators to digest, said Stevenson, who manages the Santiam Water Control District in Stayton, Ore.

“I’m optimistic it started some good conversations,” he said. “What came out of the sausage maker at the end, I’m not so confident.”

Making sense of the numerous bills introduced in the Legislature is hard enough, let alone staying on top of all the revisions that emerge from behind-the-scenes negotiations, he said.

“It’s hard to keep up with everything and provide good input,” Stevenson said. “You have to proactively keep track of each of those amendments, and what’s dropped and what’s changed.”

Sweeping water law revisions

Budget constraints prevented Oregon from investing as much in water projects in 2025 as in past years, but that didn’t hinder legislative action on the policy front.

Indeed, lawmakers passed a series of water law reforms on a scale that hasn’t even been attempted in recent memory.

Legislation approved this year aims to streamline the state’s water bureaucracy, speed up the resolution of water conflicts, revamp water investment procedures, prevent groundwater pollution and develop innovative water management tools.

Of course, that does not mean that advocates representing irrigators, conservationists, cities and other water users are entirely thrilled with the reforms enacted this year.

But given the pressures on Oregon water supplies and problems with existing processes, it was preferable to err on the side of taking action, said Rep. Mark Owens, R-Crane, a chief advocate for modernizing state water management.

“Eventually, policy makers need to make policy and move forward. You are never going to get everyone comfortable with every decision,” he said. “If we got anything wrong, which we probably did, we can address that in 2027 or ’29.”

Spurring policy reforms

This legislative session proved conducive to extensive water policy reforms partly due to the confidence gained by Owens and Rep. Ken Helm, D-Beaverton — co-chairs of the House Agriculture Committee — after five years of working together, he said.

At the same time, state revenues available for water investments were limited but the office of Gov. Tina Kotek was eager to make water administration more efficient, Owens said.

The Oregon Water Resources Department and other natural resource agencies were willing to cooperate with lawmakers to a degree that hadn’t been seen before, largely due to Kotek’s insistence, he said.

“Most of that was from the executive level,” Owens said.

Streamlining measures

A pair of House Bills, 3342 and 3544, sponsored by Owens and Helm make a long list of revisions meant to remove obstacles that slow down water rights applications and disputes, which have caused a persistent backlog of cases at OWRD.

House Bill 3342 includes minor technical fixes, such as simplifying notice requirements and allowing credit card payments.

But the bill also takes steps to discourage water speculation — the practice of obtaining water rights permits without actually developing irrigation, hoping they’ll become more valuable over time.

One of the more controversial aspects of the bill has been dubbed “automatic denials,” under which the OWRD can reject well-drilling applications in groundwater restricted areas without fully analyzing them.

The bill is supposed to prevent the agency from wasting time on proposals that would inevitably be denied anyway, but the Northeast Oregon Water Association fears automatic denials will give OWRD too much power while “squashing innovation.”

When the agency is forced to substantiate why it rejected an application, that at least provides applicants a decision they can appeal and hold regulators accountable for their analysis, said J.R. Cook, the group’s director.

The new procedure eliminates that “legal pathway,” Cook said. “You’re giving the bureaucracy a get-out-of jail-free card to never really have to work with you. That is not efficiency, that is just deference.”

Balancing efficiency with due process

Owens said he tried to address the Northeast Oregon Water Association’s concerns by narrowing the type of transactions subject to automatic denials and excluding projects that recharge aquifers or otherwise mitigate groundwater withdrawals.

Similarly, House Bill 3544 limits the time frame and arguments available for contesting water rights decisions, relying on legal precedents rather than in-depth analysis to resolve cases more quickly. Both agriculture and environmental groups have criticized aspects of the bill for hindering due process.

Owens said the legislation attempts to balance efficiency with due process as much as possible, but ultimately responds to a problem faced by the same organizations: Water rights administration is taking too long.

“The number one complaint we heard, we tried to address with these two bills,” he said.

Two water bills prioritized by Gov. Kotek — SB 1153, which imposed environmental reviews on certain water transfers, and SB 1154, which strengthened groundwater quality protections — were both subject to fierce debate this year.

In the end, lawmakers opted not to vote on SB 1153 or any other bills altering water transfer law, while SB 1154 was scaled back to neutralize opposition from agricultural groups, disappointing some environmental proponents of the bill.

Negotiations resulted in a welcome outcome on the groundwater protections bill, particularly as it will require investigation of all factors leading to aquifer pollution — such as septic tank leakage — for which agriculture is often blamed, said Cook of the Northeast Oregon Water Association.

“As a whole, we think the bill has some solid foundations,” he said. “If everyone needs to look in the mirror, everyone needs to be part of the solution.”

Commercial irrigation with domestic wells

In a move that frustrated the Oregon Farm Bureau and other critics, lawmakers allowed domestic wells to be used for commercial irrigation under House Bill 3372.

Proponents of the bill said it makes no sense to allow a wide range of commercial uses for domestic well water while singling out small farmers by effectively prohibiting the sale of homegrown fruits and vegetables.

However, critics argued the bill could exacerbate groundwater depletion without any oversight from regulators and will favor hobby farmers over commercial operators who invested time and money for water rights.

The Oregon Water Resources Congress, which represents irrigation districts, didn’t take a position on the bill as it didn’t directly affect its members, said April Snell, the group’s executive director.

Despite the organization’s neutrality, Snell said HB 3372 raises questions about the wisdom of subjecting various types of water users to divergent standards.

“It doesn’t seem very strategic to provide expanded exemptions while we are curtailing other water users,” she said.

Water grant overhaul

Criticism of how Oregon disburses water supply project grants helped spur a proposal to overhaul how those investments are evaluated.

House Bill 3364 initially overhauled the existing system for scoring and ranking proposals, but those provisions came under fire from environmental groups, who worried the public benefits of water projects wouldn’t sufficiently weigh on funding decisions.

The final version of the bill scrapped those changes, instead increasing the opportunity for public input on project rankings and allowing those comments to be considered in funding decisions.

However, the time for receiving comments was cut in half under the bill, which also expanded the types of projects eligible for feasibility study grants and reduced the amount of matching funds required of applicants.

The improvements to the grant process ended up being “modest” but should help irrigators navigate the funding process better, said Snell.

A new requirement for periodic reports to the Legislature will offer the chance to further enhance the grant process, whose current form could use streamlining, she said. “It is overly complicated and that is daunting for applicants and there are issues for the agency to review everything.”

Pilot programs for new tools

Less controversially, lawmakers approved two pilot programs in the Deschutes and Walla Walla basins that provide new water management tools and may eventually be expanded to other regions.

Under Senate Bill 761, farmers who implement conservation practices will be able to split their water rights, leasing the amount of water they’ve saved even while continuing to irrigate orchards in the Walla Walla basin.

Splits that allow continued irrigation are currently prohibited to prevent the inadvertent enlargement of water rights, but proponents of the bill say the method can provide environmental benefits without actually increasing the amount of water consumed.

Another pilot program in the Deschutes basin, authorized under House Bill 3806, would establish a “water bank” in the region, which would act as a clearinghouse for transactions among irrigators, consolidating them for easier approval by OWRD.

“The concept is very laudable,” Snell said. “However, its utility as a model remains to be seen.”

Lawmakers also instructed state agencies to focus and collaborate more on water recycling projects, such as those that reuse treated wastewater for irrigation under House Bill 2169.

Some lawmakers grumbled that it shouldn’t be necessary to force government officials to cooperate on water reuse regulations, but even they ultimately voted in favor of the bill, which allocated $300,000 for an interagency team leader to oversee the effort.

“While it’s a small bill in many ways, it’s a positive bill and we are supportive of it,” Snell said.

Funding and fees

In terms of funding, lawmakers approved roughly $27 million in new water spending this year, including $10 million for grants focused on water supply, feasibility studies and well repairs, and $7.5 million in direct appropriations for specific water projects.

To compare, the Legislature allocated about $110 million for water spending in 2023 and about $530 million 2021, though a sizable portion of that funding came from federal stimulus funds for COVID recovery.

State and federal funding is crucial for irrigation districts to modernize their infrastructure, as they lack the financial resources to fully shoulder such projects themselves, said Stevenson of the Santiam Water Control District.

“Without a continued financial commitment, we are not going to see the efficiencies we need,” he said.

For example, the Santiam Water Control District would need $66 million to replace about 114 miles of open ditches and canals with pipelines, which saves water by preventing seepage and evaporation, Stevenson said.

“Our 17,000 irrigated acres can’t support a $66 million investment, so how do you ever make that happen?” he asked.

Water fee hikes

Fees for water transactions were proposed to increase by 135% early in the legislative session, alarming farm groups, but thanks to a general fund subsidy, the hikes were limited to 50%.

That’s still uncomfortably expensive for water users, who already pay fees in the thousands of dollars for common transactions, but Snell said “the alternative would have been much worse.”

With the failure of new restrictions on water transfers, which farm groups feared would paralyze such transactions, and revisions to the groundwater protection proposal, agriculture managed to dodge some bullets this year, she said.

“I wouldn’t say it was a great session, by any stretch, but it could have been a lot worse,” Snell said.

Read more at: https://capitalpress.com/2025/08/21/sweeping-changes-to-oregon-water-law-approved-in-2025/

Photo: Brent Stevenson, manager of the Santiam Water Control District, points to equipment that helps monitor stream flow and automatically adjust the head gate at the district’s water intake diversion. Tracking the bills affecting irrigation through the Oregon Legislature is a tough task, especially since many are subject to several amendments. (Mateusz Perkowski/Capital Press)